November 24, 2022

Read a story about the origins of the Seventh Doctor's companion Ace, written by the actress who played her, Sophie Aldred!

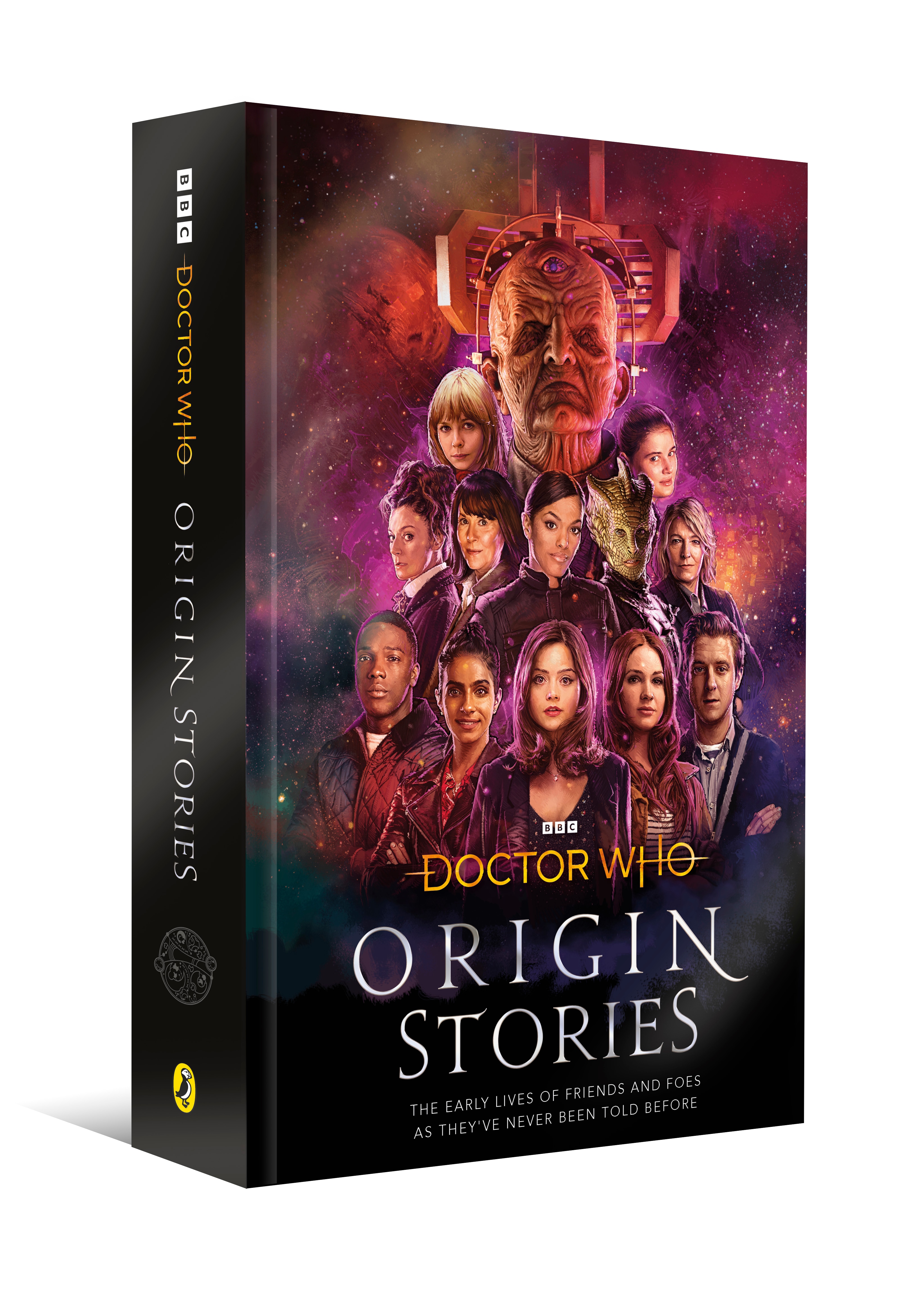

The recently released omnibus book collection Origin Stories contains eleven incredible stories from the world of Doctor Who - the early lives of friends and foes that have never been told before.

Amy Pond looks for her Raggedy Man, Jo Grant remembers her childhood, the Master hunts the past . . . and a young girl discovers a love for explosives.

You can read Chemistry by Sophie Aldred below (or you can get the novel and find the full collection here.)

The girl with the high ponytail sat scuffing her shoes on the legs of the plastic chair outside the head’s office, a familiar conversation banging around her brain.

It’s not my fault . . . it was a complete accident. Why do these things always happen to me? I couldn’t help it if Form Five’s pottery pig collection just happened to be out on the shelf where I put my stuff. It’s not fair . . .

She knew excuses or moaning would do nothing to help her already precarious position with the powers that be. So she tried to prepare a proper apology in her head, and ready herself for whatever rubbish punishment would be handed out. At least she’d had plenty of practice at fixing her face into a look of sincere contrition.

And it really hadn’t been her fault this time. In fact, her experiment had been encouraged by her science teacher, who she reckoned was the only adult in the school (maybe the only adult she’d ever met, apart from her nan) who seemed to get her. Her teacher understood what made her tick, and why she’d want to be experimenting with chemicals in the first place.

The teacher had only joined the school a few months back. The ancient, crabby chemistry teacher, who had been there for as long as anyone could remember, and who spent lessons behind his copy of New Scientist (which was surely a joke, there was nothing ‘new’ about him), had disappeared quite suddenly – no questions asked. And the teacher who replaced him was entirely different: youngish, full of energy, asked brilliant questions which didn’t seem to require sensible answers, and didn’t just read out a page number in the O- level textbook and leave the class to get on with it.

Chemistry was the one and only subject that the girl actually wanted to understand, to study. Not for any stupid exam, but because of the fact that two substances could change into something else entirely when you put them together fascinated her. Everything in the whole universe, she discovered, was made up of tiny, tiny particles: atoms and molecules. Just little dots. When you broke everything down to its basic components, there was really not much there except space. That made her feel safe, somehow.

Like looking up at the stars. At least, those nights when you could actually see them through the grime and dirty cloud cover of a West London sky. It somehow made her feel small and insignificant – and that was a good thing. By comparison, the problems and anxieties (which she never admitted to anyone, not even to herself half the time) that occasionally reared up and ambushed her in the night seemed unimportant.

She had fallen in love with the periodic table the moment she turned a page and saw the different-coloured boxes, all ordered in groups, with their numbers, symbols and weights. She would pore over it, rolling the more difficult names around in her mouth, not knowing if she was pronouncing them right. She knew how to say palladium though; that was easy. It was the name of a famous theatre in the West End. When she was little, her nan had stopped smoking for weeks and saved up for two tickets to see Aladdin at the Palladium starring Nan’s favourite bloke off the telly, Danny La Rue. They’d both shouted themselves hoarse ‘HE’S BEHIND YOU!’, and went home down Oxford Street on the bus in the dark, the Christmas lights twinkling overhead and the shop windows full of stuff she could only ever dream of having in her stocking.

Then there were all the obvious elements, of course: gold, silver, mercury, lead. But what about zirconium (which sounded more like a science-fiction villain – the Mysterons in Captain Scarlet, maybe). Or thorium (that one made her think of Norse myths). She particularly liked the sound of the planet ones, neptunium and plutonium.

She’d cut the periodic table out of her textbook and stuck it to some card with cow gum. As she covered it with sticky-backed plastic, she ran her thumb over the surface to smooth out the air bubbles, thinking about how pleased Blue Peter presenter Janet Ellis would be with her efforts.

She placed it proudly on her desk, and her new science teacher spotted it during the very first lesson. No one had ever admired anything she’d done before (at her school, teachers had lost the will to teach and praise, as much as the pupils had lost the urge to learn and behave) and so she started to ask the teacher tentative questions about chemistry.

Her friends were puzzled at first. Midge took the mick, and Shreela did a lot of eye-rolling and shrugging. But she didn’t care. Someone she quite liked had information she was actually interested in, admired her work and, what’s more, seemed to show an interest in teaching her something rather than telling her off. She found herself hanging around the lab during breaks, getting answers to her many questions. She was shocked to find she actually enjoyed spending time with a teacher, of all people.

And this teacher had more energy than anyone she’d ever met: running about the lab, pulling out books, jabbing fingers at relevant paragraphs, rushing over to the store cupboard and bringing various pots and beakers to the bench. And talking. By golly, there was lots of talking. Strange stories (some of them even nearly made sense) and all of it fascinating, thrilling, exciting. Together they wrote equations, the teacher conjuring numbers and letters out of the air and putting them together to form magic formulae. They’d turn these into substances that would transform before her eyes, with smells both good and bad, and colours and flashes brighter than anything she’d seen before.

But best of all was the day when she had worked out a brand-new recipe for a rather effective explosive, based on nitrogen. By herself.

And once she’d come up with the recipe, her teacher had given her a history lesson! With all sorts of warnings and mutterings about responsibility and codes of honour. Yes, she did know about Guy Fawkes and the trouble he got into (although she was a bit confused when the teacher started describing Guy as an ‘all right bloke, really’). And yes, although she wasn’t the biggest fan of Maggie Thatcher, she had been shocked when that hotel in Brighton had been blown up a few years back.

She promised her teacher – cross her heart and hope to die – that she would never use this explosive new knowledge for destructive purposes. That she would certainly never tell anyone about it, and that she would most definitely not make the recipe at home. If only the teacher had spotted that this last promise was made with her fingers firmly crossed behind her back.

She could hardly wait for the buzzer signalling the end of lessons that day, and ran all the way home to the flat, not even waiting for Midge, Shreela, Derek and the rest of the gang.

The container would have to be metal and it would have to look cool.

She searched the kitchen and eventually found what she was looking for at the back of the fridge: a squirty cream canister left over from Nan’s birthday, when they were being posh and had trifle. In her bedroom she took out her penknife and started scratching off all the outer plastic covering – the logos, the pictures of cows. After a lot of careful scraping she was soon left with what could only be described as a wicked- looking can.

She took goggles and gloves from her school bag, and extracted the recipe ingredients, being super careful to keep them separate. She was pleased with herself that she’d nicked all this from under the teacher’s nose . . . but then she felt an uncomfortable sensation, one she wasn’t used to.

She remembered that the chemistry teacher was the only adult, other than her nan, whose opinion she valued and for whom (it dawned on her suddenly) she’d do anything. But she had crossed her fingers, after all.

Though her bedroom was a tip, she knew exactly where everything was, from the festering T-shirts strewn across the floor, down to the three mouldy coffee cups lurking under her bed. She swiped a pile of stuff off her bedside table, carefully placed the chemicals on top and gingerly measured and decanted everything into the can. She would have to do some careful research on fuses and a timing device but, for now, this would do.

She picked up one of the T-shirts from its place on the floor, wrapped it carefully round the can, and then slipped it back into her school bag. There. All done and no mishaps. Tomorrow, at school, she would find a place to stash the can so she could work on the timer at her leisure. Now there was just enough time to run up to the youth club and see who was around before Nan came over and the evening was taken up with tea and Corrie.

She changed out of her school uniform and grabbed her signature jacket from the back of the bedroom door. That black puffy flight jacket was her pride and joy. She’d saved up enough money from her horrible paper round to buy it from Millets . . . and then started collecting badges, safety pins and other cool things to decorate it with. She’d got the idea from a very trendy magazine, spotted while she’d been collecting the papers from the cruddy newsagent. She’d never seen a magazine like that before and had spent several minutes flicking through the pages. It was a door into another world – one where she could only dream of belonging. There were so many bands, most of which she’d never heard of, and photos of so many beautiful people: girls out clubbing, wearing these puffy jackets, baseball caps and cycling shorts. She thought perhaps she could try recreating the look, even if she could never be in a cool band or go to expensive clubs. Then annoying Mr Corner Shop had shouted at her to get her grubby paws off the mags and get on with her job. She’d rolled her eyes, tutted, picked up her heavy paper-round bag and flounced out of the door.

But since then she’d done her best, on a limited budget, to emulate those girls. Yes, she got some looks from the gang at first, but she could tell that, secretly, they thought she looked wicked.

When she got to the club it was deserted. The gang must have gone to the mouldy old shopping precinct to eat chips and hang out. Well, she couldn’t be bothered with that this evening. She walked on up the hill, past all the scrappy places where people dumped crisp packets and empty cider bottles. Only slightly out of breath, she stood at the top.

The sparse trees were jagged and black, their twisty shapes silhouetted against the darkening winter sky. Down below, the lights were just beginning to come on in the estates, and out along Western Avenue, illuminating the road as it snaked out of London towards the new motorway that had just been built to circle right round the city. She hadn’t been up here for ages. It was actually quite beautiful, in its way.

Then something down near the road bridge caught her eye. Squinting in the gloom, she spotted something she’d never noticed before. It looked like a blue version of a phone box, with a light on top that was flashing on and off. How odd.

She’d been that way hundreds of times when she went to visit her mate Derek, who lived on the other side of the A40 (the posh bit near the golf course). She made up her mind to go and take a look before tea – there would be just enough time before Nan started to worry.

Scrambling back down the path in the gathering gloom, a thought struck her. She should really come clean about that whole ‘fingers behind the back’ thing with the science teacher. Her face suddenly felt hot, and her stomach clenched uncomfortably. This was a new and unusual sensation.

Usually she was quite happy to be ‘economical with the truth’ (as that politician had so tricksily put it). It basically meant lying, but now all the kids at school were saying it as it sounded so much cleverer than ‘I lied’.

But there was something different about lying to an adult who you respected and admired, and who had actually gone out of their way to give you a helping hand in life. Well, tomorrow, she’d put that right. She would go straight to the lab (the teacher seemed to prefer hanging out there to sitting in the staffroom) and make a heartfelt and genuine apology and hand over the can.

On she went, feeling slightly relieved. Past the houses, through the playground (giving the obligatory push to the roundabout as she went) and across the playing field towards the bridge. But when she arrived, there was just the same old graffitied bit of wall, the bin surrounded by rubbish . . . and no sign of the blue phone box. Strange. She had good eyesight and was pretty sure about what she’d seen. She’d ask Derek at school tomorrow; he might know something.

Now it really was getting dark, so she turned back and hurried home by the light of the street lamps.

After a fitful night’s sleep and no breakfast (the milk had gone off and there was no bread) she hurried to school to make her ‘confession’. Arriving outside the lab, she double-checked her bag for the carefully wrapped can. Having spent the night justifying her actions to herself, her new plan was to hand it over with a winning grin, say ‘Pressie for you!’ and saunter off to assembly, no questions asked. It was funny how, now it came to it, she didn’t really want to make a big fuss of things, after all.

However, best-laid plans and all that.

When she got to the lab, she pressed her nose against the square of safety glass in the door and peered left and right.

Usually, the teacher would be leaping around the room, muttering and gesticulating to no one at all, stopping to write frantic notes in a scrappy book grabbed from a seemingly bottomless pocket. Then, when she’d spotted her at the door, waving her in to show her some new find or an amazing equation. But, to her dismay, there emerged from the storeroom a grizzled, stout figure in a shabby lab coat holding a pile of dog-eared textbooks, which he started distributing ever so slowly among the lab benches. Of her beloved teacher there was no sign.

So she would have to put up with a supply teacher reading from the textbook. Boring, boring, same old, same old. It felt as if someone had taken the stuffing out of her and she groaned out loud.

Then she remembered the can.

As the day went on, she realised there was no way she could put it back. The old supply teacher might seem doddery, but he had eyes like a hawk and rarely left the lab. She hurried along there in her lunch break to find him sitting, spotted handkerchief tucked into his collar as a napkin, Tupperware box open on the desk in front of him, munching through what smelled like tuna sandwiches. She beat a hasty retreat.

She couldn’t take the can home, either, because she really had no idea if it was safe – and if it was going to go off then (a) school would be the best place for an explosion and (b) it couldn’t be traced back to her.

The gang were beginning to wonder why she hadn’t put her bag down all day. She even took it to the dining hall for the nasty stew that was served up as lunch (along with something passing for mash, plonked on to the plate with an ice-cream scoop). Midge started teasing her, until good old Shreela stepped in, sensing there was something secret going on and that her best chance of being in on it would be to back up her friend. She took Midge aside and started whispering loudly. Something about ‘time of the month’, ‘endometriosis’, and finally ‘back off, you idiot’. Midge went a lovely shade of lobster and promptly backed off.

Double art after lunch provided an opportunity at last. Mrs Parkinson did a great impression of a hippy art

teacher, in her saggy dungarees and swathes of headscarves. Until there was any hint of trouble. Then she turned into a raptor. Luckily, it was lino-cutting that afternoon. So there was a diversion when Sticky Luke managed to gouge out a sizeable chunk of thumb, having made the rookie lino-cutter’s mistake of putting his hand in front of the blade instead of behind it. As Mrs Parkinson spent many minutes holding Luke’s bleeding hand up in the air (to stop the bleeding) and berating the whole class for not listening to her safety warnings, the girl saw her moment. Reaching into her bag, she gingerly eased the T-shirt-wrapped canister up and out and slipped it on to a shelf behind some lumpy, recently glazed clay objects (so ugly and misshapen that no one would be taking them home to show Mum any time soon). Her plan was to come back the following week when, she hoped, the proper science teacher would be back from being ill or away or whatever was the problem, and deal with it then.

But next week came, and the supply teacher was still there, and no one seemed to know what was happening. When she asked Einstein (as they had newly nicknamed the supply teacher) he said it was none of her business and to get back to page fifty-four. No amount of scowling seemed to make any difference.

And then the following week the art room blew up.

Well, that was an exaggeration, but it had made a pretty good bang. The misshapen clay lumps had turned out to be Form Five’s prized pottery pig collection (who knew?).

Fortunately, no one had been in the art room at the time of the explosion. Unfortunately for her, large pieces of her easily identifiable T-shirt had been strewn around, along with lumps of pig.

The worst thing was that no one had really said anything to her at the time. A letter had been sent home (that had been easy enough to intercept) and there were mutterings of police involvement. But that hadn’t led to anything, luckily, and she thought she’d got away with it. Yet here she was, waiting for the inevitable Big Trouble she was undoubtedly in.

‘Dorothy!’

The headmaster’s voice made her jump. And wince.

How she hated that name. She stopped kicking the chair legs, put on her best ‘I’m ashamed of what I did and I’ll never do it again’ face, pulled up her socks, adjusted her school tie to normal and opened the door.

He sat behind the large imposing desk, eyes lowered, tapping a pen, slowly and annoyingly, on a large old book in front of him.

‘So. Dorothy. Again. What do you have to say for yourself this time?’

‘I’m sorry, sir. I can guarantee that it will never happen again. It was an accident and I didn’t mean to do it.’

He put down the pen – painfully slowly – his gaze still lowered.

‘Well, well. What are we going to do with you? It seems you just cannot be trusted. This . . . creation of yours. What do you call it?’

‘Nitro 9, sir.’

‘Yes, most ingenious. And you really came up with it all by yourself ?’

A pause. And now she too lowered her gaze, giving herself time to think. If she said anything about the science teacher’s help, it would be curtains for them both.

‘Well, that tells me a lot. About you. Loyal, bright, trustworthy up to a point.’

A look of confusion mixed with a certain amount of surprise spread across her face. What the heck was this about? She’d expected the usual ‘don’t do it again, hundreds of lines to write out, staying in at break for the next year’ routine.

‘How about you tell me everything you know about your science teacher? And if the information proves useful, we might be able to come to . . . some arrangement, that doesn’t involve further investigation.’

She took in a sharp breath. She would never agree to tell on the teacher. And yet, it was such an easy way of getting off scot-free . . .

‘I’m sorry, Mr Michaels, I’m not sure what you mean. The teacher was in the lab with me the whole time and was really good at health and safety. Everything I did, I did myself. It was all my fault. I worked it all out and made it and I’m sorry I nicked the chemicals and I’ll pay for all the damage and . . .’ She trailed off, realising Mr Michaels wasn’t the slightest bit interested in what she was saying.

And it was at that moment, as she at last raised her eyes to his, that she realised there was something really weird going on. The knot in her stomach turned into a less definable sensation. Surprised, she guessed this must be the rarely felt emotion (for her, at least) of fear.

For the man, if indeed it was a man, sitting in front of her and doing his best Mr Michaels impersonation, was not the world-weary, slightly dog-eared headmaster of countless boring assemblies and many tellings-off. It was something her brain couldn’t quite twist itself around. For a start, Mr Michaels, unless she had missed something, did not normally have scary shiny red eyes and puffy cheeks that were getting puffier by the second.

He, or rather it (the resemblance to a human being was now distinctly shaky), slammed what looked like giant paws – with claws beginning to sprout from them – hard on the desk as he rose out of the chair. The cheap nylon suit and tie once inhabited by the hapless Mr Michaels began to rip and tear as the body inside it grew and morphed and transmogrified into . . . Well, the girl had no idea what it was. She stood frozen to the spot, at once scared yet strangely fascinated to see what would happen next. The creature (all vestiges of Mr Michaels had disappeared) raised its . . . what? Front legs? Arms? Tentacles? A great howling wind started whipping around the office, gathering up papers, books, pens and pencils and whirling them into a mini tornado. She watched transfixed as the whirlwind came towards her, not knowing what to do and unable to move as the creature’s red eyes seemed to pin her to the spot.

There was a sudden bang behind her, which broke the spell, and she turned her head. There, framed in the doorway, was a familiar figure, long grey-blue coat flapping, boots planted firmly on the ground, arms braced against the door frame, blond bob blown about by the wind.

‘ACE! WHEN I SAY RUN, RUN!’ she shouted into the tornado . . . ‘RUUUN!’

Ace didn’t need any more prompting. The creature had now grown almost as tall as the ceiling and the tornado was getting larger and more furious, as though it was about to whip her up into it. She darted towards the door, struggling against the swirl of the wind pulling at her heels. The science teacher held out a hand which Ace caught, and she was dragged into the corridor, just as the teacher threw something from one of her bottomless pockets into the room, before slamming the door behind them.

There was a sizzling sound and then a pop and then all went quiet.

‘And that, my dear Ace, is the end of that!’ The teacher beamed, her brown eyes twinkling.

‘What the heck?’ said Ace. ‘End of what, exactly?’

‘Although, strictly speaking,’ the teacher went on, ‘it’s actually the beginning. Of everything. Of the future you. Or is it the past? It’s so confusing sometimes. Time is a many-splendoured thing when you really stop and take a look.’

‘But hang on, what about that . . . thing in there? And the wind and everything? And what’s happened to Mr Michaels?’

The teacher took a deep breath. ‘Last things first. Thirdly, Mr Michaels is right now boring the socks off Class 7B with a general knowledge quiz. Secondly, the wind and stuff was a mini time storm conjured up by an old acquaintance of mine and easily got rid of by the temporal retrorsus manipulator I threw at it (I knew that would come in handy one day). And firstly, that poor creature was definitely nothing to do with Mr Michaels – though it was using a clone of his body which must have been very uncomfy; tight and itchy, I imagine, for a Charvalian . . .’

She paused for breath. Ace’s mouth remained open but of words there was no sign.

‘Anyway. You don’t need to worry about any of it. Your bit happens later; we’re not quite ready for you yet. Or me, come to think of it. Well, me as I am now. It’s complicated.’

‘You’re telling me . . .’ Ace croaked.

‘Thing is, Ace,’ continued the teacher, getting more serious now and putting both hands firmly on Ace’s shoulders, ‘you will have a part to play, a very important part. And although I have to go now, I promise you, cross my hearts and hope to die, we will meet again. It won’t be me . . . well, it will be, but you won’t see this particular me till you’re really quite old. Old compared to now, I mean, not old old, but you know what I mean . . .’

‘I have no idea what you mean!’ exclaimed Ace. ‘You are making no sense and I don’t understand any of it.’

The teacher smiled kindly into Ace’s eyes and suddenly looked very ancient, very wise and very tired.

‘I have to go now,’ she sighed, ‘and you won’t be seeing me here again. But I want you to promise me that you will stay as brilliant as you are, always ask questions, always go for it. Because you are an ace human being and you are going to have a life beyond your wildest dreams. Now, I’m so sorry I have to do this. You’re not going to remember any of this, but there is a really good reason and it will all work out in the end. It always does.’

As Ace opened her mouth to remonstrate, the teacher swiftly placed her hands on either side of Ace’s head, and all at once she felt a warm peace running through her whole body, rather like drinking hot chocolate on a frosty day . . . but even better.

And suddenly there she was, standing in the empty corridor outside Mr Michaels’ office, wondering what on earth she was doing. From the end of the corridor came a shout.

‘Ace! There you are! We’ve been looking everywhere for you. Manesha thought you must have bunked off gym cos of your “you know what”, but you weren’t in the sick room . . .’

Derek chattered on as they walked together back to the classroom block.

‘Fancy coming to the club tonight? There’s a new bloke in charge, apparently, and he’s doing some self-defence stuff. Doesn’t sound too shabby.’

There was something nagging in the back of Ace’s brain.

Something she had been meaning to ask Derek, but she couldn’t for the life of her remember what it was.

‘Sure,’ she replied, ‘don’t see why not. After all, a girl’s got to be prepared for anything these days.’

Get the full collection of Doctor Who: Origin Stories here.