October 12, 2017

With the news that the long unfinished Doctor Who story Shada, featuring Tom Baker as the Fourth Doctor, is to be finally completed, we bring you an in-depth look at the (mis)adventure from Doctor Who Magazine.

Read more about the new release of Shada on digital download/bluray and DVD here.

Time After Time was originally presented in The Essential Doctor Who: Time Lords published by Panini UK in 2016 and presents the legacy of the Douglas Adams tale which will now be completed using the original footage from 1979 and hand-drawn animation.

Pre-order the Shada DVD here (UK)

Pre-order the Shada Blu-ray here (UK)

Pre-order Shada on iTunes here (UK)

The following article is reproduced by very kind permission of the author and Doctor Who Magazine.

Time After Time

By Paul Kirkley

“The day after we finished filming Shada,” Tom Baker once claimed, “it was already mythology to me.”

Baker recorded his final scenes for the ill-fated serial on 5 November 1979. They weren’t supposed to be his final scenes, of course: with work scheduled to run into December, there was still plenty to be done. But when the cast and crew arrived at Television Centre for the next studio session they found the doors locked. Production had been halted by an industrial dispute which, depending on who you believe, may have boiled down to a row about whose job it was to move the hands on the Play School clock.

The doors were finally unlocked later that month, but BBC bosses decided to prioritise Television Centre for more ‘prestigious’ shows like Fawlty Towers and The Morecambe and Wise Christmas Special. So, despite several studio sessions and a whole week’s worth of location filming in Cambridge having been completed, Shada was cancelled. And that was seemingly that.

Except this was only the beginning of a long and extraordinary afterlife that has ironically gifted Shada a much richer legacy than many stories that did actually make it into viewers’ living rooms. While there may be many Doctor Who adventures that are better regarded, few can match Shada in terms of its sheer – thanks Tom – mythology.

Douglas Adams’ story concerned the villainous Skagra’s search for Salyavin, a notorious Time Lord criminal. Salyavin had been imprisoned by his people on Shada, their prison planet, but had escaped and was now living in retirement as Professor Chronotis at St Cedd’s College, Cambridge. Approaching the end of his regeneration cycle, Chronotis asked for the Doctor’s help in returning a stolen book called The Worshipful and Ancient Law of Gallifrey to the Time Lords. Dating back to the early days of Rassilon, the book – which had previously been kept in the Panopticon Archives, and over which time ran backwards – was also the key to the Time Lord prison.

The first attempt to salvage Shada came while the ink was still wet on the Do Not Resuscitate order: in April 1980, incoming producer John Nathan-Turner attempted to remount the story as two 50-minute episodes to be broadcast that Christmas. It was hoped recording could take place at Television Centre in October, with the only cast change being John Leeson replacing David Brierley as the voice of K9. In June, however, Nathan-Turner was informed that no studio space could be made available.

Three years later, relatively generic sequences from Shada’s location filming were used to cover Tom Baker’s absence from The Five Doctors. If anything, Shada’s contribution to the twentieth anniversary special only piqued interest in the missing story. By the mid-1980s illicit VHS copies of the existing footage were being circulated by fans, some of whom had helpfully added explanatory subtitles produced on a BBC Micro.

In 1984, former Doctor Who production assistant Snowy Lidiard-White suggested to John Nathan-Turner that Shada might be a candidate for the BBC’s new range of Doctor Who home videos. “We’re toying with the idea of getting Colin [Baker] to fill in the missing bits with commentary,” Nathan-Turner told a convention audience the following year – possibly in the form of specially filmed scenes in which the current Doctor would recount the adventure to his companion Peri (Nicola Bryant). Once again, however, the idea came to nothing.

Shada’s next reappearance came in an even more unexpected form, when Douglas Adams cannibalised parts of his script – including Professor Chronotis, no longer a Time Lord but still a Cambridge academic with a time machine in his study – for his 1987 novel Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency. Two decades later, the book would be adapted for BBC Radio 4, starring Henry Enfield as Gently and Andrew Sachs as Chronotis.

By late 1991, fans had gone without new Doctor Who for two years. But Nathan-Turner hadn’t given up on the show – or Shada – just yet. In his new role administering the BBC’s range of Doctor Who video and audio cassettes, he concocted another plan to bring the long-lost story to the screen.

“This time I was determined,” he said, as part of the memoirs he wrote for Doctor Who Magazine in 1997.

“I persuaded Tom to do the linking material. Actually, Tom was quite keen – he told me he’d always liked this particular story, and he suggested that his links were done in the first person.”

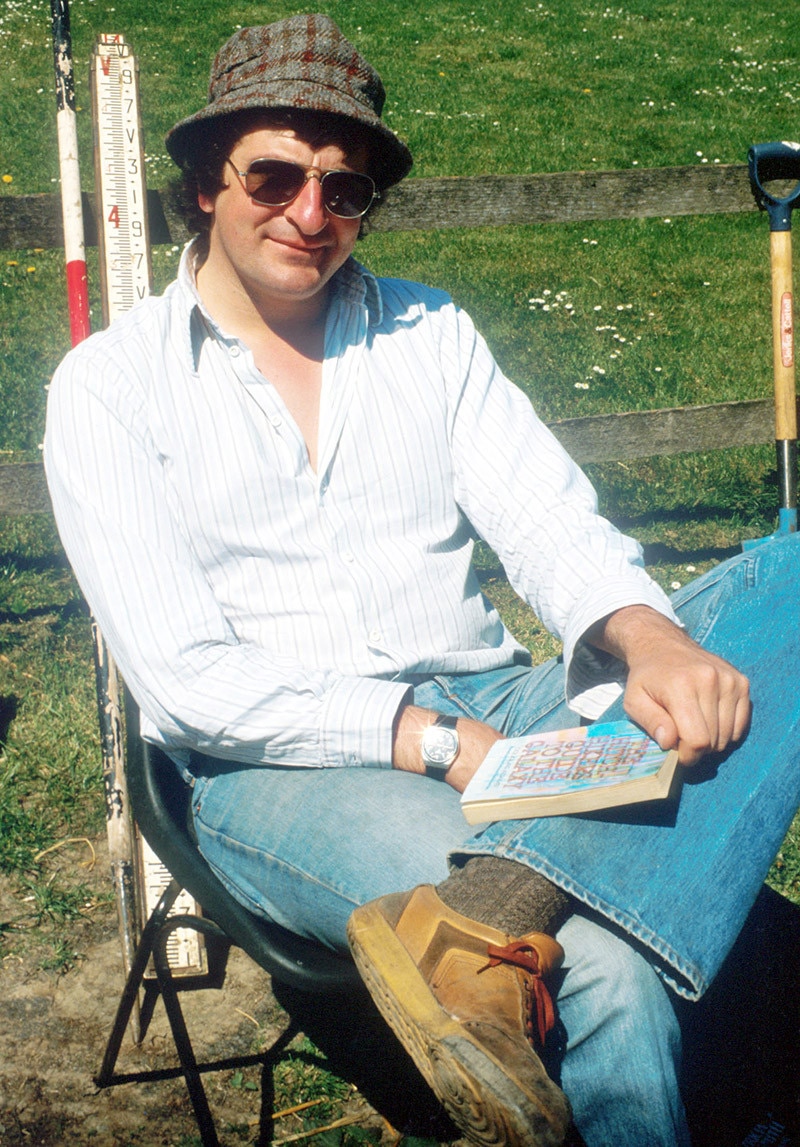

Baker recorded his on-camera narration – in character, but not in costume – at London’s Museum of the Moving Image on 4 February 1992.

“We wanted to avoid the sort of dull presentation you see so often on television these days,” Baker told DWM at the time.

“We wanted something fresher, more dynamic, if you like. They were my memories, not some unconnected presenter’s. I talked about it on and off for ages, because everyone who worked on it in 1979 realised it was so valuable. We always thought it was a terrible sadness. I don’t suppose it could have been released without some kind of links, and so we’ve sort of made it into a collector’s item."

“I was extremely pleased with it,” wrote Nathan-Turner, who also commissioned new visual and sound effects along with a score composed by Keff McCulloch.

“What was originally filmed and recorded amounted to the bulk of Part One, less of Part Two, even less of Part Three and so on, resulting in very little for Part Six! I took liberties with what was available from the archives; I split scenes, I invented backgrounds, I used material unintended for transmission, so the tape didn’t conclude with little more than a ‘talking head’ – even if it was Tom Baker’s.”

Someone who was less than pleased was Douglas Adams. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy author had written the script in a frantic hurry to fill a hole at the end of the season, later describing his effort as “a mediocre four-parter stretched over six weeks."

Adams was equally lukewarm about any efforts to revive Shada. “The story was a bit of a patchwork quilt to begin with,” he said in 1990, “so making a patchwork quilt out of the remains of a patchwork quilt would produce something very peculiar indeed.” In fact, he was so horrified by the idea of Shada being stitched together for video like some kind of Frankenstein’s monster (according to some reports, he signed over his permission for the project by accident) he refused to have his name appear on the cover. He donated his fee to Comic Relief.

The video was packaged with a miniature copy of the script and released on 6 July that year – finally appearing on viewers’ screens a mere 4,918 days later than originally planned.

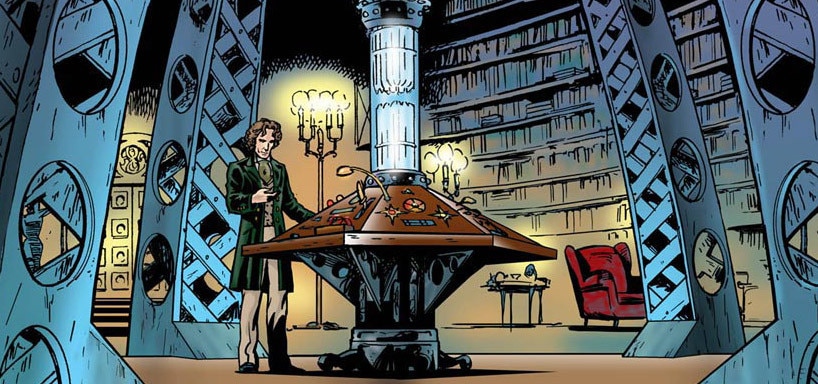

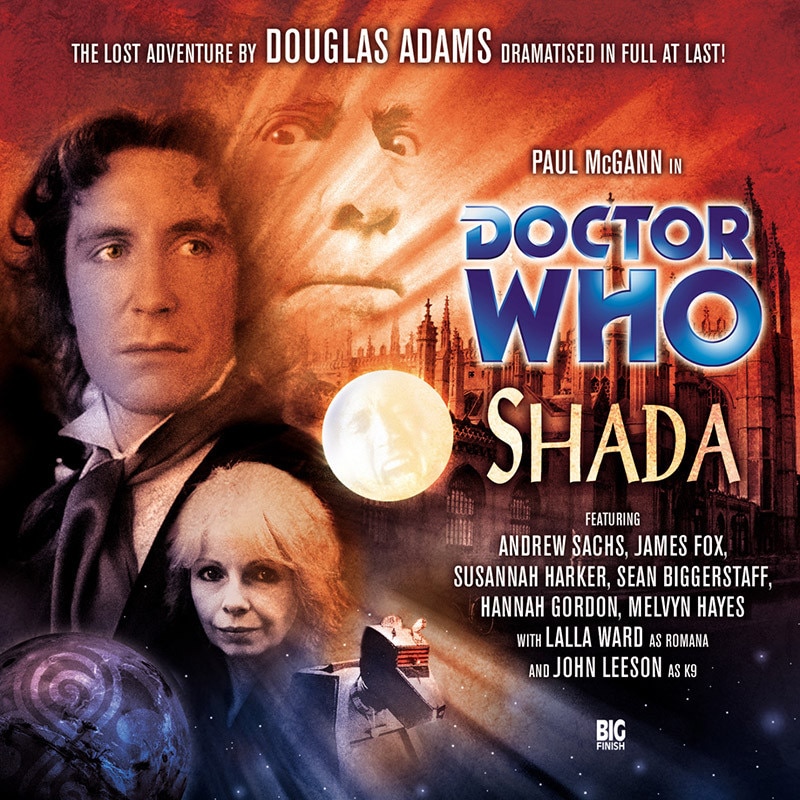

It would be another decade before Shada reared its head again. This time the initiative was led by James Goss at BBCi, as the BBC’s digital operation was then known. Goss approached Gary Russell and Jason Haigh-Ellery of Doctor Who audio producers Big Finish with the idea of recording Shada as a webcast to mark the series’ fortieth anniversary in 2003.

“We’d already done [Sixth Doctor webcast] Real Time with BBCi,” recalls Gary. “Jason had had dealings with Douglas’ estate and was on good terms with them, so he had a relatively easy time getting the agreement to do it. There seem to have been lots of myths over the years about the estate being evasive or tricky, but we found them delightful, encouraging and pleasant. They even suggested finding out if there were earlier drafts of scripts to see if there was anything exorcised we might want to put back in, even if it was just odd lines.”

Lalla Ward, who played Romana, declared herself perfectly happy to work with Tom Baker again, even though she hadn’t seen her ex-husband for more than 20 years. In the end, however, Gary adapted the script for Paul McGann’s Eighth Doctor.

“I knew I could get Paul McGann’s voice into it rather than just have him say lines originally written for Tom,” Gary explains. “It didn’t need much alteration – I mean, it’s Douglas Adams for heaven’s sake, it’s as close to perfect as it’s ever going to be. But there were subtle nuances in delivery and flow that I opted to make more McGann-esque.

“Then there was just the task of audio-ising some of the more visual bits, and I had to create the opening few minutes with Romana and the Eighth Doctor, to explain why we were doing Shada all over again. That was fun. After that I handed it over to Nick Pegg, the director, and wished him well!”

McGann, Ward and John Leeson were joined by an impressive cast, including James Fox as Chronotis, Andrew Sachs (as Skagra in this version), Susannah Harker, Melvyn Hayes and Hannah Gordon. Flash animation featuring illustrations by Lee Sullivan completed an impressive package, which was made available in six instalments through May and June 2003, and later released on CD.

Did it feel strange for Lalla Ward to be recreating those scenes with a new Doctor? “Everything about Doctor Who is pretty strange,” she says, laughing.

“This didn’t seem any stranger than other strangenesses. It was lovely to return to a story I had always liked – largely because of Douglas – and with not just the good fortune to be working with Paul, but with an amazing cast altogether. The actual filming of the original Shada wasn’t altogether easy – filming never is – so in many ways I had a much happier time on this.”

Tom’s are big shoes to fill – does Lalla think Paul McGann succeeded in putting his own stamp on it? “I don’t think any version of the Doctor is to do with filling shoes,” she says. “You can only bring your own take to it and find a new pair of shoes.”

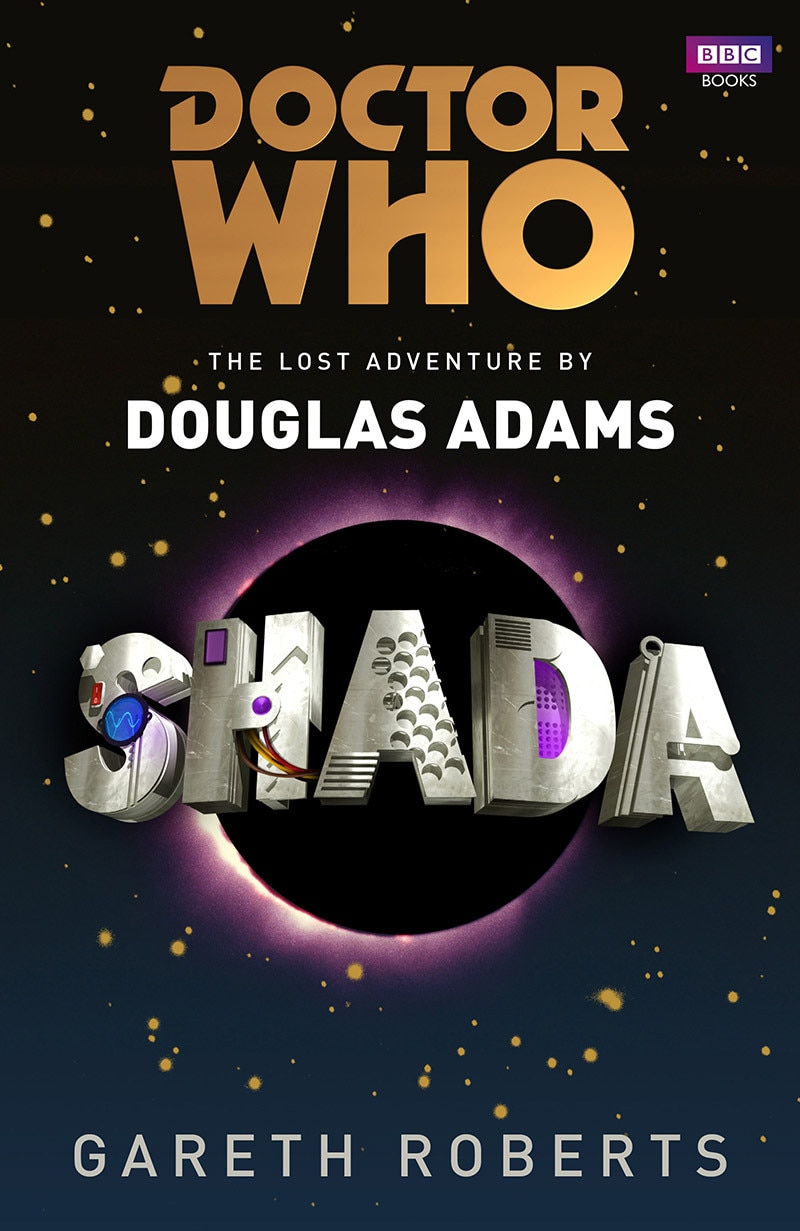

That advice might have proved equally useful to Gareth Roberts when, in late 2010, he was asked to adapt Adams’ Shada scripts into a novel.

Roberts was a natural choice: as well as being one of Doctor Who’s wittiest scriptwriters, he had penned several well-received novels based on his personal dream team of the Fourth Doctor and Romana II, and had long been a cheerleader for that period of the programme. Despite this, by his own admission, the book proved to be the toughest challenge of his career.

“It was very much harder than I was expecting,” he says. “I thought, ‘The story’s all there, the dialogue’s all there, it’ll be a doddle.’ But the story didn’t make much sense. That’s not me going, ‘I’m better than Douglas Adams!’ – it was just that you could tell it had been written very, very quickly. So although it’s brilliant, it was hanging out all over the place.”

Honoured and daunted in equal measure, Gareth didn’t attempt to emulate Adams’ style, (“I gave up on that idea at the very beginning”) and says he was left to get on with it by the late writer’s estate. “They stood well back, really. To be frank, because it was a Douglas Adams project, I thought it might go bigger in the publishing world. But it was really Doctor Who first, Douglas Adams second, and anything with ‘Doctor Who’ on it is never going to be a massive bestseller. Which is a shame!”

Despite the labour pains, Gareth was happy with the finished novel. “Looking back, I think I did it pretty well, really,” he says. Lalla Ward, who performed the audiobook reading, agrees. “I thought Gareth did a really good job of it,” she says. “Very clever, very Douglas. I think Douglas would have been impressed.”

The following year Shada was issued on DVD, packaged with thirtieth anniversary documentary More Than 30 Years in the TARDIS as a box set entitled The Legacy Collection. The main feature was a reissue of the VHS edition, albeit brought up to current technical standards with new transfers from film negatives.

At one point, the producers of the DVD had entered into discussions with fan and former continuity adviser Ian Levine about featuring an unofficial version of Shada he had financed himself. As well as new animation to cover the missing scenes, Levine had reconvened many of the original cast – though, crucially, not Tom Baker – to record their lines from the abandoned studio sessions. It was ultimately decided to stick with the 1992 version.

“We are here to restore, as best as possible, content that’s in existence,” the DVD’s commissioning editor Dan Hall told DWM at the time. “It’s not our role to create what was never there. Shada is a great unfinished story, but it’s just that – unfinished. Creating brand-new Doctor Who editorial content is the remit of the BBC, not BBC Worldwide.”

One of the bonus features, Taken out of Time, saw several of the cast and crew returning to Cambridge to discuss the making of the story, and its aftermath.

“You always look forward to the ones where something went wrong!” says Chris Chapman, who produced and directed the documentary. “Going into it, we knew we had some meat – the very fact it was cancelled meant we had a really good story to tell. We didn’t really have to coax stories out of anyone,” he continues. “For the people who experienced Shada at the time, it’s a big memory. For Tom… he doesn’t always have very clear memories of individual stories, but he remembered Shada very vividly, because of Cambridge and Douglas, and because of how it turned out.”

In retrospect, one of the most poignant aspects of Shada’s cancellation was that the serial was supposed to serve as the Doctor Who swansong both for Douglas Adams and producer Graham Williams – two men who, as Tom Baker reflects sadly in Taken out of Time, died at a young age. With the abandonment of Shada it was left to the underwhelming The Horns of Nimon to bring the curtain down on 1970s Doctor Who, before John Nathan-Turner brought in sweeping changes for the start of the new decade.

For all its writer’s reservations, Doctor Who’s most tantalising near-miss has proved exceptionally enduring over the years. It could even be argued that cancellation did Shada something of a favour. “It has had a strange afterlife,” says Gareth Roberts, “and one of my main aims [with the novel] was to finish that off! People were so much more obsessed with it because it hadn’t been made than they would have been if it had. I thought it was time to move on. Which was absolutely bonkers – people are never going to move on from Shada.”

Lalla Ward was good friends with Douglas Adams up until his death in 2001. She feels he would have been “intrigued by the life of this once-doomed story… I think it would have had a particular interest to people anyway, because it was so ‘Douglasy’, but its chequered history has certainly added to its allure.”

“It’s partly to do with Douglas dying and partly to do with Shada itself dying a young man’s death,” she says. “It was like a poet dying young, or Marc Bolan. They take on a sort of mythical quality. And no doubt Shada will continue making myths for many years to come.”

One man who had reason to be thankful for Shada’s cancellation was Terrance Dicks. By the start of 1983, the veteran writer had just about managed to juggle all the characters and elements required for the show’s 20th Anniversary Special, The Five Doctors, into a workable script. At which point, Tom Baker decided not to take part. “I discovered that there’s a bit of Shada where Tom could be picked up, and another where he could be released,” Terrance told Doctor Who Magazine in 1998. “So I said, ‘I’ll trap the bugger in a time loop, and that will be him gone from the rest of the show.’”

And so it was that The Five Doctors saw two location sequences from Shada – one of the Doctor and Romana punting on the River Cam, and another of them leaving in the TARDIS – finally making it to air. “It went like clockwork,” said Terrance. “Actually, I think it improved the story.”

A notable story in the DVD documentary Taken Out Of Time is the revelation that Daniel Hill, who played student Chris Parsons, married production assistant Olivia Bazalgette after meeting her in Cambridge during the filming of Shada. The couple went on to have three children together. If you’re looking for the ultimate proof of Shada’s afterlife, it’s surely that there are people in the world who owe their existence to that heady week by the Cam in the winter of 1979.

“That was such a gift,” says the documentary’s producer/director Chris Chapman. “We went to Daniel and he said, ‘Are you going to speak to Olivia, too?’ And I didn’t know why he was talking about Olivia. But that was lovely – it meant that, despite it all going wrong, there was a sense of something good that came of it.”

This article was originally presented in The Essential Doctor Who: Time Lords published by Panini UK in 2016.

Special thanks to Doctor Who Magazine, Peter Ware and Paul Kirkley.