October 22, 2021

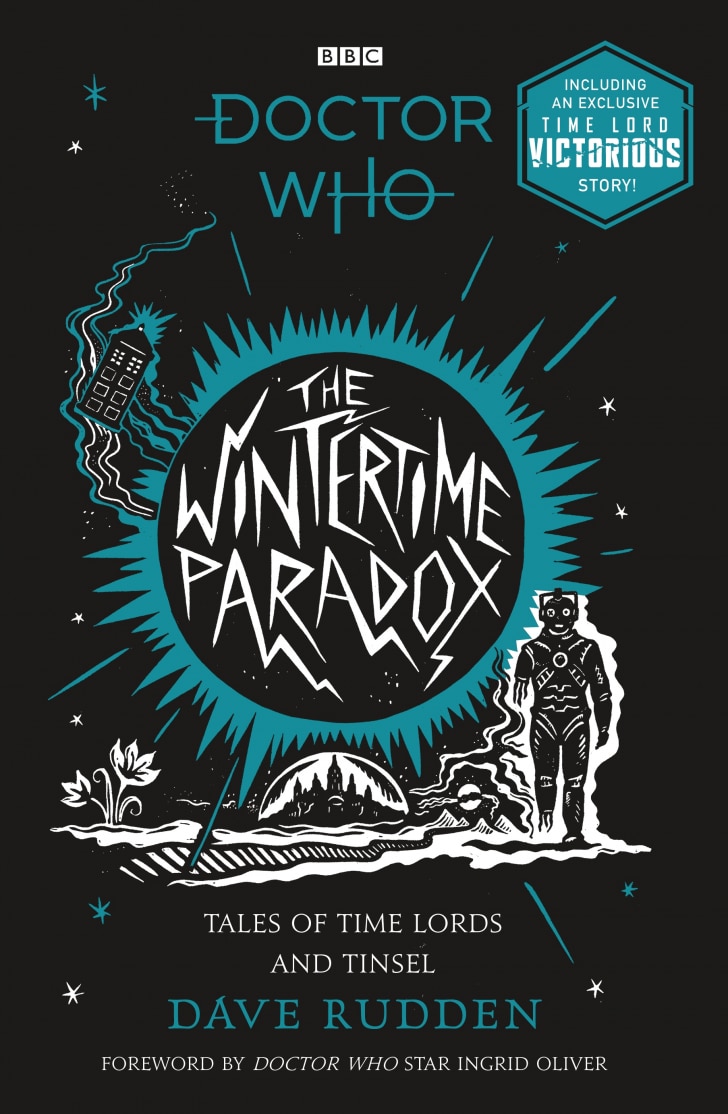

Fancy a Ninth Doctor adventure? Read the full story A Day To Yourselves, from The Wintertime Paradox, available now as a paperback.

Get more festive tales in The Wintertime Paradox, out now

A Day To Yourselves

The engines roared, and time roared back, washing over the hull of the TARDIS in waves of icy blue and burning gold. Reality unfolded for the spinning wooden box, funnelling it through a storm of seconds, then folding back into place as neat as wrapping paper.

The Doctor swept through the doors, wearing his best and fiercest grin.

‘Hello,’ he said grandly. ‘I’m the Doctor, and I’m here to save the world.’

‘That’s nice,’ said the receptionist. ‘And, tell me, do you have an appointment?’

The Doctor’s grin faltered, then he rallied, straightening the lapels of his black leather jacket. ‘Well, I’m a time traveller,’ he said jauntily. ‘I don’t really do appointments.’

That usually got a reaction. It was one of the Doctor’s favourite details about the universe outside Gallifrey, as well as one of the things he found most confusing. Time travel was, to Time Lords, about as exciting as the postal service. It was mostly cheap, mostly reliable, and everyone used it. Yes, sometimes it took an awfully long time to get to the desired destination, and sometimes things went spectacularly wrong but, all in all, it was just a thing that happened, and you were a bit weird if you talked about it too much, particularly at parties. Non-Gallifreyans, however, genuinely believed time travel was magic, while ignoring the far more impressive inventions of their own cultures. Such as, for example, a delivery system where one paid a pound to have a folded piece of paper inside another folded piece of paper taken from Bingley to Guam.

If the receptionist was impressed, he was doing a very good job of hiding it. His wrinkled face was set in the grimly pleasant expression common to all receptionists when dealing with the unwashed, appointment-less masses. This was another little detail the Doctor found interesting: whether you were dealing with a nine-foot-tall receptionist samurai on Hegetory Prime or the planet-sized Appointmentrix of the Wailing Twelve, there was a look. They all had it. He’d always meant to take a weekend to investigate why, but he’d presumably have to make an appointment to do so.

‘I’m afraid you need an appointment. We have a very packed morning here at Moveomax Holiday Cards,’ he said, checking the inlaid screen on his desk.

His name tag said winston. Winston was not a nine- foot-tall receptionist samurai, disappointingly, but Moveomax Holiday Cards was apparently the kind of company that invested in their employees, and eight segmented metal arms branched from his shoulders, each one stamped with the Moveomax company logo.

‘Ah,’ the Doctor replied. ‘I understand. Except, wait. Because I don’t.’ He looked around. ‘Isn’t there some sort of . . . emergency you need help with?’

The receptionist followed his gaze around the waiting room. Moveomax Holiday Cards was at the forefront of the twenty-fourth century’s holographic personalised greeting- card industry. The Doctor knew this fact because it was emblazoned on the wall in migraine-bright letters. Below these letters was a small, hard couch, a coffee table with a framed selection of bestselling cards and a potted plant. Dracaena marginata, the Doctor guessed. Unfortunately, aside from the plant being a little underwatered, there was a distinct lack of emergency to be had.

‘I don’t think so,’ Winston said. ‘Sorry.’

The Doctor’s frown deepened. ‘Well, I don’t mean specifically in here.’ He tried once more to inject some jauntiness into his voice. ‘I don’t really do office emergencies. Generally, the emergencies I fix are a little more . . . global.’

Winston sniffed. ‘We trade on seventeen planets, you know.’

‘Oh no,’ the Doctor said hastily. ‘I didn’t mean to insult you.’

He was getting frustrated, and took a moment to remind himself that getting frustrated was good, actually. Frustration, he had decided, was something this version of the Doctor was going to feel a lot, because frustration meant he wasn’t winning. The Doctor had won a war recently; now he never wanted to win anything ever again.

He picked up the little flip calendar sitting on the receptionist’s desk. It was Moveomax-branded, and the picture of Santa on the front was animated, moving back and forth and waving at the Doctor. The Santa was Moveomax- branded too.

‘It’s the twenty-third of December, isn’t it?’ the Doctor said. ‘In the year 2321? And this is the planet Eirene?

Galactic coordinates 51–2–89–14:02? Past the wobbly red star and that comet with all the yellow bits?’ ‘This is Eirene, and that is the date,’ Winston confirmed. ‘I’m not one hundred per cent sure about all the other words that you said.’

‘OK, good,’ the Doctor said. ‘Marvellous. Fantastic. It’s just . . . you’re really supposed to be getting invaded right now.’

The receptionist checked his screen again.

The Doctor waited patiently, or as patiently as the Doctor ever waited for anything. This meant that he fidgeted a lot, unfolded and refolded his arms several times, and absent-mindedly worked out Eirene’s axial tilt based on the position of the sun and how long it had been since Winston’s mechanical arms had been tuned up.

Winston’s fifth and sixth arms readjusted his glasses. ‘I’m afraid I don’t have anything under “invasion”.’

‘Really?’ the Doctor said. ‘It’s a Gnarlmind invasion, if that’s any good to you? Kind of like rats, but worse. Giant rats. In spaceships. Think it’s supposed to kick off around two?’

The receptionist thought for a moment. ‘Oh! Oh, yes. Large rat things. I remember now.’

‘Phew,’ the Doctor said, sagging with relief. ‘So, if you could just point me to –’

‘It’s all been sorted actually,’ Winston said. ‘Thank you very much, though.’

‘Sorted?’ the Doctor said. ‘What do you mean, “sorted”? It isn’t a printer jam.’ He caught himself. This frustration thing was taking a while to get used to. ‘Sorry. It’s just there’s supposed to be about forty-three million of them. I had this whole big speech prepared about how, in the face of a horde, it only takes one person to make a difference. Who sorted it?’

‘A man,’ Winston said. ‘He didn’t have an appointment, either.’ His eyes drifted across the Doctor’s battered leather jacket. ‘Though he was better dressed. He had a suit. Brightly coloured shoes. More . . .’ He cleared his throat. ‘Taller hair.’

The Doctor rubbed his scalp self-consciously. Some said regeneration was a lottery, but at least with lotteries you got to enter once a week and try your luck again.

‘He didn’t leave his name, unfortunately,’ Winston continued. ‘It was all a bit exciting. But he did have a box. A box just like yours, actually.’

He pointed at the TARDIS. ‘Oh,’ the Doctor said. ‘Oh. I see.’

‘Now that I think of it, he said someone might be dropping by.’ Winston laced four hands pensively under his chin. ‘And I believe he left you a . . .’

He turned to the shelf behind him, retrieving a blue pinstriped envelope with a single word scribbled on the front.

When he turned back round, the man and the box were gone.

Oh well, the Doctor thought, as the TARDIS plunged once more through the vortex of everything that was, will be or could be. Bound to happen sometime, right?

It was. It definitely was. The universe was large – really, truly, gigantically large – but it wasn’t so large that coincidences didn’t happen. He was always running into people from his past. And from his future, come to that. He’d even run into himself a few times, though that was usually only on special occasions. It was what happened when you had very specific interests – a bit like comic books, or Chibolg Mega-Stamps. There just weren’t that many people interested in the same thing, so you inevitably ended up crossing paths with one another.

It stood to reason that, eventually, another version of himself would accidentally poach his adventure.

‘Bound to happen,’ he said, out loud this time.

The words echoed around the control room. There was nobody else to hear them. The Doctor usually travelled with people. Travelling with people was half the fun. If Peri was here, or Jo, or Sarah Jane, they could have had a laugh about the stiff, confused look on Winston’s face. If the Brigadier was there, the Doctor could have had a laugh about it and the Brigadier could have scowled at him good-naturedly. Leela might have offered to stab Winston, and they could have had a jolly old laugh about that, too.

‘I’d even settle for Adric,’ the Doctor said glumly.

This was no good at all. It was nearly Christmas, or at least it had been on Eirene. The Doctor decided then and there that it would be Christmas for him too, because one benefit of living in a time machine was that you had Christmas pretty much on tap.

‘I’m going to save someone’s Christmas,’ he said jauntily, and that made him feel a little better. He needed to put things out of his head. Move on. Keep moving, as far as he could.

‘Bound to happen,’ he said again, and pulled a lever to take both him and the thought away.

Wind moaned through the Crystal Sphere of Zed Trief.

No one knew who had made the sphere, or set it spinning through the void. It was one of this sector’s great mysteries: where had the night-black sphere come from? Who had carved the mirror-smooth tunnels through its core? To some cultures on neighbouring planets, the sphere was a bad omen, appearing at the end of every year like a miserable aunt. To others, it was a symbol of the universe’s fundamental impermanence, how even beings powerful enough to create such a sphere could be forgotten in time. To the Cult of the Breaking Sunset, it was home.

Dark and mysterious rituals required dark and mysterious spaces, so the fanatical brotherhood had plumbed the depths of Zed Trief, turning its chambers into chapels, fortifying its surface, installing stolen weapon platforms. The sphere had been a bad omen. Now it was a fortress.

Or so the Doctor had heard, anyway. He neatly bypassed every single one of the cult’s security measures by materialising the TARDIS right in the middle of the sphere’s great central chamber. More specifically, he materialised it right on top of the Grand Hierophant’s black stone altar, knocking over some very ornate candleholders.

A thousand cultists paused mid-chant. The Hierophant, already a little top-heavy because of her crown, fell off her chair.

‘Hello!’ shouted the Doctor.

For all their many faults, the cult had picked an excellent spot to hold their sinister get-togethers. This was the largest chamber beneath the sphere’s surface – a great circular cavern large enough to hold several football fields (should the Cult of the Breaking Sunset ever decide to get a match going) and so acoustically perfect even the slightest whisper carried.

‘I’m the Doctor, and I’ve come to stop your terrible plan!’ He paused. ‘You are doing a terrible plan, aren’t you?’

Silence. The Doctor rubbed the back of his neck. ‘And the entrance? The entrance was OK, wasn’t it? Sorry, it’s been a bit of a morning.’

‘I thought it was very good,’ the Grand Hierophant said from the floor. Her features, like those of her congregation, were hidden beneath the hood of a voluminous black robe. The Doctor liked black robes. No self-respecting cult skimped on the robes.

The Grand Hierophant sat up, straightening her crown. ‘Although . . .’

The Doctor hopped from one foot to the other self- consciously. ‘Although?’

‘I’m not quite sure we are doing a terrible plan, unfortunately.’ The Grand Hierophant had the careful, surprisingly smooth voice of a community-club organiser, the kind of voice that took notes on meetings, got the proper insurance and remembered to put out biscuits. Good voices were also necessary when it came to running cults.

‘Well, you would say that, wouldn’t you!’ the Doctor crowed triumphantly. ‘You’re the Cult of the Breaking Sunset. Worshippers of the universe’s ending. You’ve chosen the last days of the thirty-third century to steal the Globe of Unmaking from the vaults of the Shemi-Goroth, and now you’re going to use it to punch a hole through reality itself!’ He took a breath. ‘Aren’t you?’

The Grand Hierophant had the grace to look embarrassed. ‘No. Sorry.’

The Doctor sat down hard on the lip of the black stone altar. ‘Oh,’ he said. ‘I had a suspicion. Didn’t see a Globe of Unmaking anywhere.’ He picked at a bit of congealed candle wax with his finger. ‘Can I ask why not?’

‘Well, for a start,’ the Grand Hierophant said, ‘we’re not the Cult of the Breaking Sunset. We’re the Order of the Knotted Fate.’

‘Blessed be,’ said the congregation.

‘The Cult of the Breaking Sunset were the last tenants. Left the place in an awful state too, I don’t mind telling you. We recycled the robes because, well, they’re nice robes, but we threw out all the skulls and candles because they weren’t really in keeping with the whole Knotted Fate thing.’

‘Blessed be,’ said the congregation again.

The Doctor gave them a look. ‘And so you stopped them?’

‘Oh my, no,’ the Grand Hierophant said. ‘We just moved in when it looked like they weren’t coming back. I wasn’t actually here but –’ she looked around, then pointed at a hulking figure in a hooded robe identical to all the other hooded robes in the chamber – ‘you were, Clodus, weren’t you?’ She leaned in conspiratorially. ‘Clodus was in the Cult of the Breaking Sunset. Now, he’s on the side of the Knotted Fate. Aren’t you?’

The huge figure shrugged. ‘Just like keeping busy, your grace.’

‘What happened?’ asked the Doctor. He was getting frustrated again. This was what happened when you tried to go somewhere specific, instead of taking the universe how it came. Getting your dates wrong, well, that wasn’t the worst thing. There were a lot of dates. It was hard to pick the right one. But he’d always wanted to see a Globe of Unmaking, a piece of technology that made a TARDIS look young. But now the globe was gone, like so much else, and the Doctor had missed it.

‘A man came,’ Clodus said, scratching his head through his hood. ‘He interrupted the Elder Magnificant just as she was about to activate the globe, then gave the whole cult this big dramatic speech –’

Clodus pointed – ‘right where you’re standing. And then it turned out that he’d done something to the globe’s circuitry and, rather than poking a hole in the universe like it was supposed to, it just unmade itself. He said it was –’ the Doctor could practically hear Clodus’s brow furrowing in the depths of his hood – ‘cascade polarity reversal.’

‘Cascade polarity reversal,’ the congregation repeated as one.

‘After that, we all started thinking that maybe it was fate that the universe hadn’t ended, and then me and the boys thought maybe we should find a new cult –’

‘Order,’ the Grand Hierophant interrupted. ‘Order sounds better, Clodus.’

‘As you say, Elder Magnifican–’ Clodus cleared his throat.

The Doctor was sure that, within the confines of her hood, the Grand Hierophant was scowling.

‘Um. Grand Hierophant,’ Clodus went on. ‘And, by the time we thought to look for him, the man was gone.’

‘And tell me,’ the Doctor said, pinching the bridge of his nose. ‘Did this man also have a blue box?’

A ripple of nods went through the chamber.

‘We thought about adopting it as a symbol,’ said the Grand Hierophant. ‘But then we thought about the other thing he said, and we decided that this might be more appropriate.’ The Grand Hierophant pulled down her hood, revealing a face as wrinkled and shiny as an old apple, her hair a dandelion mass of white wispy curls.

The other cultists pulled their hoods down too. They were all wearing bow ties.

‘Bow ties are cool,’ the Grand Hierophant said a little sheepishly, but the Doctor was already flinging open the doors of the TARDIS. Then he turned as if a thought had just occurred to him. ‘Did he say anything? This stranger?’

The Grand Hierophant held out a red envelope. ‘He gave me this. In case – and I quote – “the grumpy one with the big ears” showed up.’

The Doctor stared at the envelope suspiciously. ‘What is it?’

‘I think,’ the Grand Hierophant said, ‘he called it a Christmas card.’

The TARDIS spun. Outside, whole aeons flew by. Flocks of minutes whirled like spooked sparrows. Centuries pattered like raindrops against the doors. The inside of the TARDIS was just as complicated as the vortex swirling around it. The Time Lords had built the TARDISes, but it was more accurate to say they had grown them. Planting a seed didn’t mean you knew where every bud would bloom or where each vine would curl. There were places in the TARDIS that even the Doctor didn’t know. There were rooms he had never been in.

There was one room he thought he might never go in again.

The door to this room wasn’t dramatic or forbidding. It wouldn’t have passed muster with any cults for dark and mysterious deeds. It was just a door, no more intimidating than the envelope in his hand, and that just went to show how misleading such things could be.

I should know better, he thought.

It was incredibly dangerous to contact your past self. Even the Doctor, who was curious in the way stars are hot and ice cream is cold, did his best not to meddle in his own timeline. Even the slightest knowledge of the next changed the now. A single bow tie could destroy the universe.

‘Twice now,’ he said. He’d gone back and retrieved the envelope from the receptionist on Eirene, mostly so he could glare at it. ‘Twice. And they’re writing to me.’

What were they thinking? Never mind reading the card – just having it was a Class Four Felony. He dreaded to think what the Time Lords’ Chancellery Guard or the Celestial Intervention Agency would have said about that. Gallifreyan law enforcement got really ratty about anyone messing with timelines. That was one of the reasons why the Doctor had enjoyed it so much. Time Lords were so solid. So sedate. The TARDISes had given them a doorway to every picosecond and planet that ever was or would be, but the Time Lords looked at those door frames and saw picture frames instead. Like the universe was just a painting on a wall – faintly interesting, but mostly decorative. So intent on taking their time, when all the Doctor wanted was to take time and do something with it. That was the seed the Time Lords had planted in him.

‘And look how that ended up,’ he said, and gave the closed door in front of him a sad little smile.

That was all over now. The Doctor would have quite relished being dragged up on charges in front of his peers – again – but there were no more Class Four Felonies to be charged with because there were no Time Lords to do the charging. There was just him. Only him. And it frightened him to death getting a card like that, because it meant that maybe this loneliness would last forever. Maybe, somewhere out there among all the minutes and seconds was a version of himself so alone they were desperate enough to send him cards.

The Doctor knelt, and carefully pushed the envelope under the door. It could sit there forever, for all he cared.

‘You’re the last person I want to talk to,’ the Doctor said, and went back to the TARDIS’s control room.

One lever hadn’t been enough last time. Now he pulled two, just to be sure.

Unfortunately, not listening to yourself cuts both ways.

The Doctor flew to the Ark of the Gammazed – that famed, failed expedition beyond the borders of the dying twenty-ninth galaxy – only to be gently told off by the ark’s captain, who was ‘doing fine, thank you,’ since a nice traveller had pointed out the flaws in the Gammazed grav-acceleration design before they caused catastrophic engine failure.

A third card took up residence in the TARDIS. The Doctor pushed that one under the door as well. Next, the X-Particle Mines. The Doctor had always wanted to visit the X-Particle Mines. It was said that, in the deepest tunnels, there were shapes. Shapes that whispered under the clatter of tools and the gasp of the particle collectors. Shapes that promised you things. Shapes that stole you away.

When the Doctor arrived, however, he learned that a nice woman in a blue box had not just rescued the missing particle miners, but had also convinced the miners and the shapes – revealed to be particle miners from another dimension tunnelling into this one – to strike for better holidays. Now the disappearances had stopped, and everyone got Sundays and Christmas off. Which was nice. The Doctor left with a plate of turkey, the beginnings of a monstrous headache, and a fourth Christmas card. It was very like collecting Chibolg Mega-Stamps, he realised, in that you swiftly wanted to kill everyone else who was doing it.

That was when he had a fantastic idea.

The Forty-Fifth Chibolg Mega-Stamps Convention was held at the Zhudash Plaza Hotel, on the sprawling city-world of Ghent. It was the most famous event concerning Chibolg Mega- Stamps – which meant that if you were in the hobby it was the event of the year, and if you were outside the hobby you had no idea it existed. This led to annual confusion among the Zhudash Plaza’s other guests, who for one weekend a year found themselves sharing the hotel with very intense beings from all over the universe who wore garments with slogans like if you want me to listen, talk about mega-stamps or i was collecting mega-stamps before it was cool! (The Doctor, on witnessing the latter T-shirt, briefly considered visiting this mythical time, but decided there were some areas of history too distant for even him to visit.)

There had been a time in Ghent’s history when it had not been a city-world, but that was long forgotten. Now, every square metre of the planet was covered in shining neon towers and oiled-brass citadels. They marched not just over the land but across the oceans, the great floating raft-districts spreading like oil slicks. Forests had been bulldozed.

Mountains had been planed flat. All for the ever-growing Megapolis of Ghent.

A hundred billion people lived in this city, and what little sky existed above the vast super-skyline was filled with circling, swooping atmosphere scrubbers, spindly as dragonflies. Their wide, thin wings were complicated arrays of smog-sieves and ash-collectors and they hummed softly as they drank in pollution and exhaled crisp, clean air.

‘You know they have to keep moving?’ the Doctor said, to nobody in particular, slinging first one leg over the hotel balcony rail, then the other. ‘It’s the way they’re designed. They never land. Never stop.’

Behind him, the opening ceremony of the convention continued. The organiser – a twitching, hissing Voord whose rubbery black skin contrasted sharply with the distinctive white gloves of a Mega-Stamp collector – was giving a speech. People sipped drinks and chatted. This was a big occasion in the world of Mega-Stamps. Everyone who was anyone was there.

I should go make friends, the Doctor thought. He was good at making friends, most of the time. Though that might have been because he usually tried to make friends when things were exploding and, if you spoke like you were an expert on why those things were exploding, people tended to listen. And, often, he did know why they were exploding, which worked out well for everybody.

Now, however, he just couldn’t bring himself to do it.

It was funny, he thought. He’d spent so much of his life running from his home world, but, now that it was gone, it was like the ground had been stolen from under his feet.

The roof of the Zhudash Plaza Hotel was 284 floors above the busy street below. Wind plucked aggressively at the Doctor’s stamps? stamps!! T-shirt. He thought about saying something clever, but then decided that there wasn’t much point if there wasn’t anybody around to hear it. Then he pushed himself off the balcony.

It was a long fall, but Zhudash Plaza had not skimped on its safety protocols. The Doctor had barely plummeted ten floors before the hotel’s lawsuit-avoidance hardware spun into life and caught him in a focused anti-grav field.

I could say something clever now, too, he thought.

Instead, he took out his sonic screwdriver and convinced the window opposite his floating form that it should be a door instead. The translucent gel that served Zhudash Plaza as glass opened in a neat circle, and the Doctor drifted through, feet touching down lightly on the carpeted floor.

‘Hmph,’ he said.

Suite 2V34 was an immense warren of complicated art and plush furniture, all carved from materials so rare they could have bought whole tower blocks anywhere else on Ghent. Wall-mounted screens played local Christmas-music videos on mute. The suite had its own kitchen, tucked away behind a holo-screen in the corner. The Doctor could hear the armed guards outside in the corridor, and gave serious thought to knocking something over so they’d rush in to capture him and he’d have someone to talk to.

He decided against it. They would have enough to deal with in a moment.

The Forty-Fifth Chibolg Mega-Stamps Convention would eventually become known as the Mega-Stamps Massacre, because the Fraternity of Keepers (who did not go for robes, but did have very sharply tailored tunics) was about to steal the Mega-Stamp commemorating the crowning of Chibolg Emperor Glin. A fierce war would break out in the wake of the theft. The hotel would be locked down for months.

That was why the Doctor was going to steal the Mega- Stamp first.

He made his way to the huge desk in the centre of the apartment, scanning it with his sonic screwdriver until he found three slight discolorations on the wood.

‘Voord finger oils,’ he murmured disinterestedly.

He held out three of his own fingers in roughly the same arrangement, pressing down on the stains until a secret hinge clicked and a panel slid back, revealing a tiny square in a glass display case.

‘The Chibolg,’ the Doctor said, ‘built the most efficient postal service in the universe. It became a species obsession – hunting for innovation, improving response times, training legions of staff – and then they all just disappeared. Vanished one day. Total mystery.’

Nobody exclaimed shock, or seemed impressed, or used this as an opportunity to tell the Doctor something about their experiences with the postal service. Nobody said anything, so the Doctor continued talking, because it was better than being silent.

He swept his sonic down the little square, then nodded. ‘I thought so. Sentient ink. That’s where the Chibolg went. Everything they were, everything they are, rendered into data and written on paper. They began posting themselves.’

He smiled. It was the first genuine smile he’d had in a while. ‘And why not? You build this amazing thing – of course you’re going to use it. Why have something so marvellous and not use it to go everywhere and see everything? Why spend any time at home at all?’

He looked closely at the little square. The tiny threads of ink were writing and rewriting themselves constantly.

‘I suppose home is what you make it,’ the Doctor said, and lifted the glass display case. ‘I suppose it only feels like home when you can’t go back.’

There was a series of clicks.

‘You’re early,’ the Doctor said, turning round to find seven guns pointing at him. ‘I wasn’t going to trip the secret alarm for another three minutes.’

‘Hello, sir,’ the leader of the security team said. The visor of her helmet danced with a glowing crosshair. ‘My name is Squad Leader Quell. We’d like you to stand down, if you don’t mind.’

‘Hi, Squad Leader Quell,’ the Doctor said. ‘Nice to meet you. I probably won’t stand down, actually, if it’s all the same to you. I think I’ll escape with this Mega-Stamp so it can’t be stolen, thus preventing all-out war.’

‘That does sound nice,’ the soldier said. ‘And what do you plan to do after that?’

The Doctor shrugged. ‘Don’t ask me this early. I never know this early.’

‘He said you’d say that.’

The translucent gel of the windows shimmered and became diamond-hard. Armoured panels crashed down over all the doors. The other members of the security team moved like the jaws of a trap, surrounding the Doctor and covering the doors.

There was a long moment of silence.

‘Was it the bow-tie one again?’ the Doctor said. ‘Because I –’

‘I don’t know anything about a bow tie, sir,’ Quell said. ‘This gentleman had a bit of an accent, sir. Sort of an angry accent. He –’

The Doctor waved his hands. ‘Don’t be specific! I can’t know specifics. I’m trying to forget the specifics I’ve already heard!’

‘Sorry, sir.’ The Doctor had never seen someone so apologetically point a gun before. The crosshairs on Quell’s visor flashed as she blinked. ‘Our orders are specific. He’s going to deal with the kerfuffle outside, and you’re going to put your feet up for Christmas.’

‘I’m what?’

‘He says you need a break. That’s what Christmas is for.’ Quell indicated the plush surroundings. ‘This suite is practically impregnable. He paid quite a lot of money for us all to train in a very expensive restaurant on Darillium, sir.

He really thinks you should take some time off, sir. He said he was trying to be nice.’

‘House arrest,’ the Doctor said disbelievingly. ‘House arrest as a Christmas present.’

The security guard looked distinctly uncomfortable. ‘I’m sorry, sir,’ Quell repeated. ‘He said you’d understand why he couldn’t say more. He said there’s a room in the blue box you won’t go into, and he says he knows why.’

The Doctor let out a long sigh. ‘All right. All right. Just let me . . .’ His eyes narrowed. ‘So you’re all highly trained, are you? Best equipment in the universe? Probably kitted out with all sorts of enhanced sensors, right?’

The security guard nodded. ‘Best money can buy, sir. Magnification of all five senses. I can hear the atmosphere scrubbers sighing two hundred feet up. I can hear the bell at reception. They’re really very strong sensors, sir.’

‘Wonderful,’ the Doctor said. ‘Fantastic.’

He pointed his sonic screwdriver at the wall-mounted screens.

‘How loud do you think these go?’

Later, the Doctor sent Quell and the whole security team boxes of chocolates as an apology. In their thank-you notes, they assured him their hearing was definitely going to come back.

They also sent him a fifth card.

And later later, when the adrenaline had worn off and the silence had returned, the nervous energy that the Doctor usually poured into bad jokes and rescuing the universe propelled him, as it always did, to the door. The door he wouldn’t open. The door he hadn’t opened since trading his former self’s clothes for a battered coat and the first T-shirt he could find, old boots crunching on a carpet of broken glass. ‘OK,’ he said. ‘Fine.’

He opened the door and stepped inside.

There were many phrases on Earth that did not translate to Gallifrey. One of those was the notion of a walk-in wardrobe. The costume room of the TARDIS was not a walk-in wardrobe; it was a walk-about wardrobe. A walk-for- miles wardrobe. Even the Doctor didn’t know how far it stretched. Sometimes he wondered whether the TARDIS was always quietly adding to it because it liked dressing him up in new clothes.

There were a lot of mirrors in the costume room. All of them were broken.

‘I’m sorry about that,’ he said.

The TARDIS did not respond, but the grumble of the engines smoothed just a little at his words. ‘I don’t even really remember doing it. My memories are fuzzier than they should be.’ He stuck a finger in his ear and wiggled it. ‘Timelines grating off each other. My future selves changing things. Messing around. Messing things up.’

He looked down at the floor.

The Time War. Gallifrey’s ending. The version of himself who did these things, and all the other versions who were to come.

‘I worry they’re still grieving.’

He noticed there was a broom in the corner. It hadn’t been there before. The timeship could have repaired all the mirrors itself, folded away the broken glass as if it had never been there, but the TARDIS knew the Doctor. It knew moving was better than standing still.

The Doctor began gently sweeping up the glass.

‘The old things feel different. My adventures don’t feel right. It’s like Gallifrey was always there. It was my forwarding address. It was the star I guided myself by, even when I didn’t agree with it, or didn’t approve of it, or defied it entirely.

Where do I go from here?’

Something caught in his broom. He looked down.

It was another envelope. Small and scuffed and brown, tucked underneath one of the largest shards of glass.

‘If I don’t want cards from my future selves,’ the Doctor said, ‘then I definitely don’t want one from you. I left you behind. You’re the me who did this. This is your fault, and now I have to clean up the mess.’ He snatched up the envelope, angry now. Angry enough to tear it open and pull out the card.

It wasn’t a Christmas card.

It was small, and Moveomax-branded. The little shape on it spun and sparkled in its field of black.

The Doctor stared at it. He had seen a lot of planets. There were square planets. Living planets. Planets made of song. He was from a planet that was as red and orange as a fire agate – so red you could almost feel its heat from space. The planet on the card was blue and green. Not particularly impressive. Not particularly large. The script on the card read wish you were here.

The Doctor looked around the room, at the costumes he had worn and might wear, and then he looked at the one place he had always gone no matter how lost he felt.

‘Home,’ the Doctor said. ‘A place that always needs saving.’

He closed the card. ‘Merry Christmas to me.’

Get more festive tales in The Wintertime Paradox, out now